Tempest Born – The Ocean Course at Kiawah Island

Pete Dye had arrived for his first look at the miles of marsh, beach, and bramble that were going to host the Ryder Cup in just two years’ time.

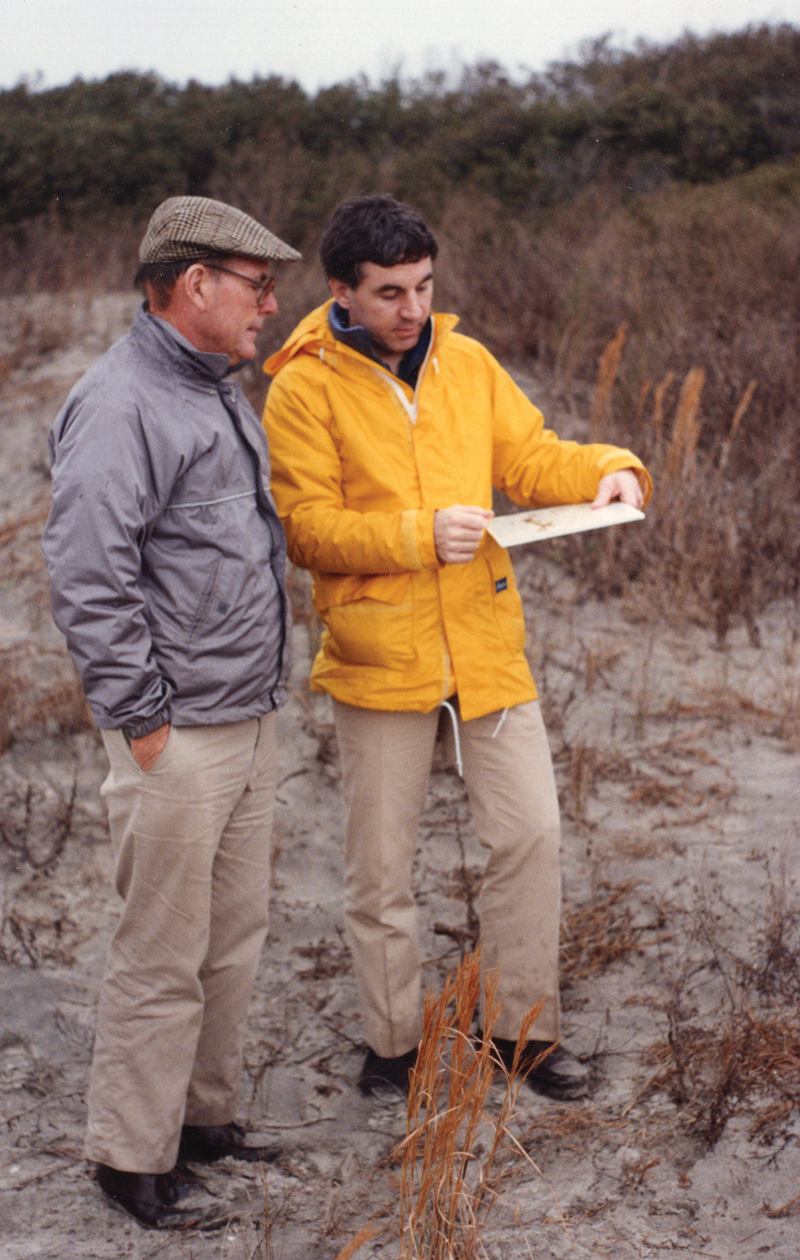

There was no stopping to ask for directions. Pete Dye had arrived for his first look at the miles of marsh, beach, and bramble that were going to host the Ryder Cup in just two years’ time, and Mark Permar had been asked to serve as his backwoods chauffeur. As the longtime land planner at Kiawah Island Real Estate, Mark knew the island’s acres better than anyone, but the undeveloped eastern edge was tricky.

“Normally, you can tell where you are at Kiawah by listening for the ocean,” Mark explained, “but we were out by the inlet, so the water was on either side of us. This is Pete Dye, so I really wanted to be on top of my game, but within thirty minutes, I got us completely lost in the middle of the thickest stuff on the island.”

In hindsight, it was a fitting start for The Ocean Course, where the property seemed to test Dye and his crew at every turn, as if to ensure they were worthy of such a rare canvas. From the site’s inaccessibility (a forty-minute daily commute through unpaved overgrowth) to the unreasonable timeline (from swamps to fairways in less than twenty-four months) to the intervention of a record-setting hurricane—The Ocean Course wanted its crew to earn it. They did, and along the way, each setback was lined with glimmers of hope and strange providence.

Mark and Pete would become dear friends over the course of Dye’s time at Kiawah, but Mark admitted, “Getting lost with Pete Dye in the truck felt like one of the great embarrassments of my life. I don’t know him from Adam at this point, and he’s grumbling in the back about where we are. But every once in a while, I’d make another wrong turn and we would bump into one of these giant sand dunes. We would stop and Pete would get out, and he would wander off. He’d walk the dunes, and you could just see him getting a sense for the size and the space of the property. I could tell he was just gathering and absorbing everything. He started to ask me questions about prevailing breezes, and I remember him saying, ‘I think we can lay this out such that you can see the ocean from every hole.’”

The Ocean Course may have been born that afternoon in 1989 with Mark lost at the wheel, but the forces behind its creation had been simmering for decades. They finally came together not in the barrier islands of South Carolina, but in a clubhouse on the west coast of England.

The result of the 1977 Ryder Cup at Royal Lytham & St. Annes Golf Club was decided before its opening ceremony began; the American side had lost the Cup to Great Britain and Ireland just once since 1935, and the biennial exhibition was slipping into competitive irrelevancy. After another breezy American victory, Jack Nicklaus lobbied the event’s hosts to rejuggle the format, and he succeeded: In the 1979 Ryder Cup, the Americans faced off against a team drawn from all of Europe, not just the British Isles.

The matches grew tighter, the rivalries more intense. Out came the flags and the chants and a new golf jingoism. A formerly polite affair of unevenly matched sides was now a gut-wrenching donnybrook. Team Europe had retained the Cup through three consecutive contests as the matches approached Kiawah, an event its promoters presciently labeled “The War by the Shore.” Had the European team not been reconstituted, however, it might have been called “Handshakes in the Desert”—the ’91 Ryder Cup had been scheduled to take place at PGA West in Palm Springs. But as the Europeans built their winning streak, international interest and viewership were spiking and a late decision moved the event to the East Coast to better accommodate European television audiences. PGA West’s parent company, Landmark Land, fortunately had an eastern site in mind for the ’91 Cup; they just had to build it first. Two years to construct a Ryder Cup venue on Kiawah wasn’t an entirely unreasonable timeline, if Mother Nature cooperated. And in the most bizarre and destructive fashion, she did.

“A group of us who were involved in the ’91 Ryder Cup went over to England to see the ’89 event,” Mark explained. “While we were over there, that’s when Hurricane Hugo hit Charleston and Kiawah. There was a press conference with the European writers about the next Cup, and they were asking if we really thought we could have the event, why the course wasn’t built yet, asking what we were going to do now that a Category 5 hurricane had hit the site. They were basically making every suggestion that this wasn’t going to possibly happen at Kiawah.”

For Mark and his team, the flight home to the States was quiet. After learning that their homes and families were safe, their attention turned to Kiawah, where Hugo had made the island entirely inaccessible.

“The downed trees and the debris, it was just awful,” he recounted. “I got a helicopter pilot to pick us up so we could survey the damage on the island, and it was extensive. We just kept going down further to the east end, where the new course was supposed to be, and we looked down—and we could not believe what we saw. There was Pete, down there on a piece of machinery, out there building the golf course.”

As if the hurricane never happened, Dye piloted a bulldozer along the beach and found himself back on the site, sculpting holes. “He was out there on a mission,” Mark said “and it got us all pumped up. We thought, ‘Hey, if he can do that, we can clean this place up, we can make this happen.’”

Pete Dye’s top man on The Ocean Course build was project manager Jason McCoy. Together, he and Pete had followed the National Guard back on to the island the morning after the storm, where they found that the dunes at the centerpiece of their course had been destroyed. But what had been left was a clear slate of ocean vistas packed with possibilities.

“There were two stages to building The Ocean Course,” Jason explained. “The first stage, we were going to build it low. With the main dune in front of us, and all the regulations for a sensitive coastal property like that, it was all we could do—build some lakes for recirculating the water, build it low and get the place going. But the hurricane hit, and life changed. The storm just changed it.”

Jason recalled placing Pete and his wife and design partner Alice into the bucket on his loader and lifting them above all the hurricane wreckage. “Alice was just struck by the beauty of everything we could see, now that the dune was blown out. And that changed how we were going to build The Ocean Course.”

Instead of building low holes along the dunes, Jason was charged with lifting the golf course and bringing the waves into view, giving The Ocean Course a character distinct from other Lowcountry layouts. Since Hugo had demolished the setting’s fragile natural features, the team’s work was now viewed as environmentally restorative instead of ecologically threatening. Not only could they now build boldly, but they could build quickly, too. From Mark getting lost in the woods to Jason growing grass in the fairways, the project was completed in less than eighteen months.

Pete Dye plus the ocean is a golf recipe hard to spoil; perhaps Kiawah’s major championship venue was bound for greatness no matter the whims of fortune or weather. But two less-often noted ingredients at The Ocean Course deserve fair credit: the marsh and Alice. And not in that order.

“The hidden jewel of Kiawah is the marshland,” Mark explained. “The contrast of the island’s beach with its marshes—it’s a really strong, if less obvious element, and I was immediately encouraged that Pete was intrigued by the marshland and was considering more than one way to look at the golf.” Along with the elevated fairways and greens, a winning feature of The Ocean Course is the way it moves along, away from, and toward the ocean, tying the beach to the rest of the island’s topography and flora. But even more essential than its look and its routing, the genius of Pete and Alice Dye’s Kiawah routing resides in the fact that, on any given morning, it could host either the PGA Championship or an outing for resort guests, and either crowd would leave feeling well served.

“That was Alice’s influence,” Jason said. “She knew golf. She understood the game from a variety of perspectives, and she didn’t forget about the shorter hitters. She wanted wider fairways where amateur players needed them. She was really smart about tee placement—they would go back and forth on ideas, Pete and Alice, because she had the same passion he did. And then they would settle on a happy medium. Or Alice would get her way.”

And the course was better for it. Whether it be the placement of the fifth hole (Alice’s idea) or the ideal balance of greens that ran right-to-left and left-to-right (Pete’s trademark), Pete and Alice were a mighty collaborative force at The Ocean Course. The fruits of their teamwork can be found at Crooked Stick or Harbour Town or Sawgrass as well, but at Kiawah, something larger resonates—something born of the unexpected, the auspicious, the celestial, even. Playing a course crafted by hand can be a powerful experience, but it’s really no match for a hurricane. — T.C.

Tempest Born

STORY by TOM COYNE

Photography courtesy of Mark Permar and Kiawah Island Golf Resort