Men at Sea

Story by Dr. Christina Rae Butler

Before refrigeration and supermarkets, before corporations and long-distance supply chains, Charleston’s seafood came from local waters, from the nets and hooks of generation after generation of hardy, dedicated fishermen.

Charleston’s Mosquito Fleet was something of a cultural phenomenon. These brave and highly skilled African American mariners fished the coastline in small, handmade boats with names like The Peerless, Victoria, Davie Jones, Ocean Queen, Match Me, and Too Sweet My Love. Onlookers from land were said to have likened the scene of tiny fishing boats with brightly colored sails to a “mass of mosquitos skimming over the water.” And so was born the Mosquito Fleet. These simple but agile crafts supplied Charleston markets with fresh fish, crab, and shrimp for centuries.

Fishermen of the early Fleet were mostly enslaved men. In 1770, the South Carolina legislature noted that “the business of fishing is principally carried on by Negroes, mulattoes, and Mestizoes.” After emancipation, the members of the Fleet were freedmen who sailed their own boats.

The Fleet’s boats ranged in size from eighteen to over thirty feet, with crews consisting of two to seven men. The crafts were designed for sailing, but they also had oars for when the sails were slack. The Mosquito Fleet built and repaired their own boats and often made their nets and rigging. In bad weather, as few as ten fishermen braved the sea, but in summer the fleet would swell to the hundreds. The boats always went out together for safety and raced to reach the best drops, or spots to anchor and drop their fishing lines.

Sailing as far as twenty miles offshore, Mosquito Fleet fishermen navigated by memory and an expert knowledge of coastal landmarks and tides. The Fleet often used shrimp as bait to catch a variety of fish, including black sea bass, porgy, whitefish, summer trout, flounder, sheepshead, snapper, mullet, redfish, croaker, and drum. The fishermen brought in an average of three hundred “packages” of fish a day, the equivalent of three railcars and seventy-five thousand pounds of seafood.

Each small squadron had their preferred launching points, including Adgers Wharf across from Rainbow Row, and further up the Cooper River where Fleet Landing restaurant is today. In the 1880s, “De Sous Bay Fleet” left from Moreland’s Wharf near the foot of Legare Street. And Cantini’s Wharf at Tradd Street and Rutledge Avenue was a popular launching point before the area was filled in the 1910s. But “Fisherman’s Pier” at the east end of Market Street was the most popular launching point over the centuries. The wooden structure was equipped with a fish basin and a large shed for the Fleet to store equipment.

Crowds gathered on the wharves to see the daily catch “or hear some fishers yarn about the leviathan who got away.” There were lively scenes each afternoon as fishermen sold their catch to seafood wholesalers and hucksters peddled foodstuffs door to door throughout the city.

In 1889, beachgoers watched in terror as a cloud burst erupted just as the Fleet cleared Drunken Dick Shoal near Sullivan’s Island; “the manner in which these daring and hardy fishermen rode the squall out was really worth seeing. They put their little boats before the wind and went racing, tearing, bobbing, bounding, dipping, and jumping through the white crested billows until they fairly outraced the storm and reached their fishing grounds. It was a thrilling sight. Not a single boat was damaged.”

Though stout, the vessels were quite small, and over the decades, many of the legendary Mosquito Fleet fishermen drowned when treacherous squalls and hurricanes swept in with little warning. The work was so dangerous that the Fleet organized a union “to care for the sick and bury the dead.” The union had over one hundred members who “brave storm, sea, and darkness so Charleston’s dinner tables might be graced by fish.” Fifty-four men died at sea between 1900 and 1931 alone.

DuBose Heyward immortalized the Fleet in his 1925 novel Porgy, which was unique for its portrayal of African American life in Charleston, and which he later adapted with Ira Gershwin into a nationally acclaimed opera, Porgy and Bess. Heyward captured the excitement, drama, and danger of the daily campaign at sea. In Porgy, news spread quickly of favorable conditions and the “crews got their boats hastily in commission and were ready to join the ‘Mosquito Fleet’ when it put to sea. When the sun rose out of the Atlantic, the thirty or forty small vessels were mere specks teetering upon the water’s rim against the red disc that forged swiftly up beyond them. Afternoon found the wharf crowded with women and children, who laughed and joked with each other as to the respective merits of their men and the luck of the boats in which they went to sea. Custom had reduced adventure to commonplace; yet it was inconceivable that men could put out, in the face of unsettled weather, for a point beyond sight of land, and exhibit no uneasiness or fear. By the time that the leisurely old city was sitting down to its breakfast, the fleet had disappeared into the horizon, and the sun had climbed over its obstructions to flood the harbor with reassuring light.”

Sadly, the march of progress took its toll on the once mighty Mosquito Fleet. Larger boats equipped with diesel engines moved in, and seafood was shipped in from around the nation. Development threatened the docks and wharves along the Cooper River. In 1959, Hurricane Gracie struck a final blow. After the storm, News and Courier reported, “all that is left of the flotilla of tiny craft which once sailed for the sea to gather blackfish, mullet, whiting, ‘cats’, and ‘swimp’ are a few rotting hulls in the mud of Fisherman’s Wharf at the east end of Market Street.” In 1960, City Council deeded the property east of East Bay Street to the Ports Authority, and the Mosquito Fleet was rendered homeless.

Charlestonians still remember the fleet fondly, and tour guides share the city’s maritime heritage with visitors, pointing to the lost Fisherman’s Wharf. In 1995, the New Charleston Mosquito Fleet was launched to mentor young people to build boats, row, and to again connect with Lowcountry waters. The final home of the Fleet, today Union Pier, is about to change once again—shifting from an industrial landscape to a mixed-use residential development. Done right, the project might provide public access to the waterfront again, in honor of the noble Mosquito Fleet.

Local writer Robert Behre notes that “many expect that one day, descendants of the men of the fleet will be able to fish, perhaps even set sail, from the same spot where their ancestors once did the same.”

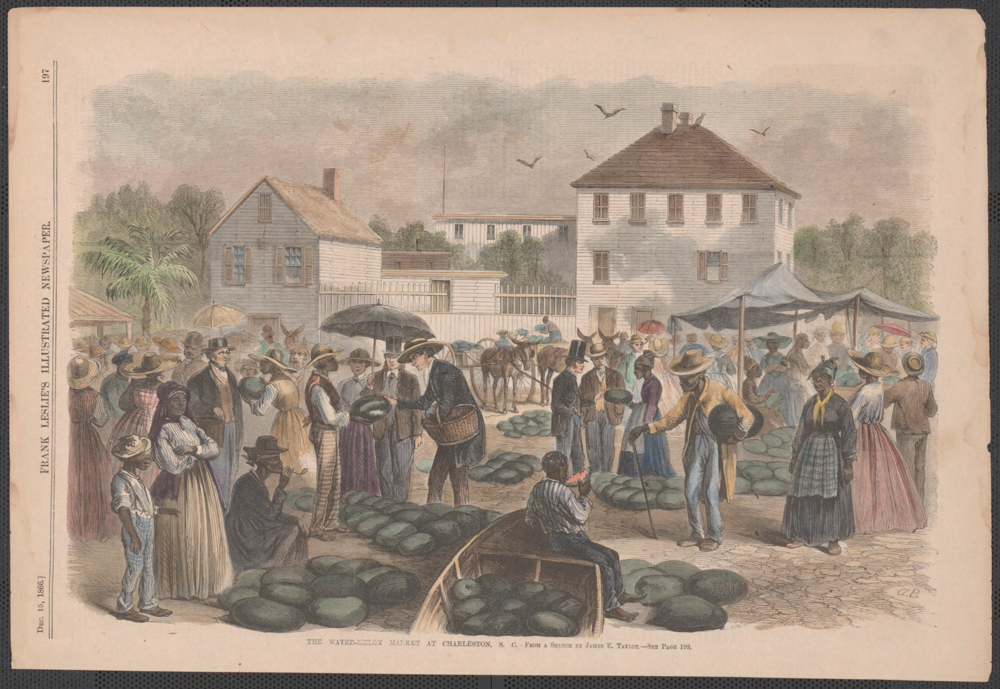

Photos From Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper and Courtesy of The Charleston Museum | Charleston, South Carolina