An Inside Look at Kiawah Island’s B-Liner Restaurant

How the B-Liner Came to Be a Club Favorite

Masterfully redesigned in a coastal chic motif, the B-Liner reflects the ever-evolving tastes of Kiawah Island Club Members, with a menu showcasing local ingredients that are expertly prepared.

James Beard Award-winning Chef Mike Lata is chef and owner of Charleston’s acclaimed FIG and The Ordinary. He has since created a menu just for the B-Liner, celebrating the Lowcountry’s best seafood, produce, grains, and meat. Here, southern culinary tradition pairs with light, fresh coastal influences in creative yet familiar dishes. A perfect complement to Kiawah Island.

The restaurant is open for brunch Saturday – Sunday 10 am to 3 pm. Lunch is served Monday, Tuesday, and Friday from 11:30 am to 3 pm. Dinner is available Friday – Tuesday from 6 pm to 9 pm.

Take an inside look at the B-Liner restaurant, as written by Hailey Wist prior to its opening.

The B-Liner’s Story

As we pick our way through the sawdusted studs of the new restaurant, Lata freestyles about the menu concept. “I want it to be very light and healthy,” he muses. “It’s going to be seafood-centric. A wood burning oven will yield some kind of flatbread, and hopefully we’ll do something with interesting grains.” But more than anything, his approach to the menu will be grounded in the quality of the ingredients and where they come from. “I don’t necessarily think about the techniques or dishes first. I curate a list of producers. I think that’s my thumbprint, right?”

It’s safe to say that Chef Mike Lata has star power. He is owner/chef of two of the most celebrated restaurants in Charleston — one of the greatest food cities on the eastern seaboard. He’s been a guest on Top Chef and Iron Chef, and his restaurants have been featured everywhere from Bon Appétit to The New York Times. He is a James Beard Award winner and has been nominated several times over.

But perhaps what makes Lata so special, really, is his impact on the local community. He pioneered the relationships that created the robust local food movement in the Lowcountry. He has helped found, or advised on, the Sustainable Seafood Initiative, Slow Food Charleston, Lowcountry Local First, and GrowFood Carolina. He has helped farmers and purveyors establish best practices and grow viable businesses. He has forged and encouraged partnerships that have made Charleston’s kitchens and restaurants what they are today.

Lata’s ethos is grounded in a deep and uncompromising commitment to place, his food a tapestry of rich and personal narratives. The B-liner will be a reflection of this. We stand in what will soon be the kitchen of the restaurant. The roof has been torn off and light streams in. Lata makes wide sweeps with his arms to indicate where the windows will go and how the line will run. “The menu will be peppered with things that are familiar, but we’ll still challenge people,” he says with a smile. “So long as the food has integrity and the ingredients are well curated.”

Abundant Seafood

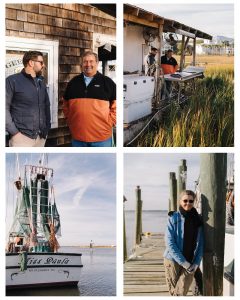

A cold December wind blows hard off the Atlantic. Mike Lata and Mark Marhefka stand in the orange, early morning sun, stamping their feet and chatting. Shem Creek is alive with seagulls and wind, and Marhefka’s men are busy at the dock, their breath clouding in the cold air.

Lata and Marhefka have an easy way with one another, and you get the sense that they have stood around like this, low-talking about food and fish, many times over. “We do break bread and talk about what’s going on in the industry,” Marhefka tells me. “We talk about what’s up-and-coming — what species are opening and closing.” This direct relationship, this open line of communication, is fundamental to the functioning of the system that Lata has created. It is the reason that his crudo tastes like nothing else in the city. “How can you beat the quality of seafood coming off this boat a mile from my restaurant,” he says. “I am talking directly to the fisherman. I mean, what’s better?”

When Marhefka came on the scene in 2007, Lata was an eager, if cautious, buyer. Working with Marhefka not only meant the freshest fish but also input on the process. Logistically, the partnership was complicated at the start. Before, Mike could get fish delivered whenever he wanted. But if Marhefka’s boat didn’t come in with fish until Friday, it meant starving the restaurant inventory until then — a lot of pressure on the kitchen.

Over time, Marhefka and Lata worked together to develop best practices. “We experimented with post-harvest handling for what seemed like years,” says Lata. “We went through the growing pains together.” But to Lata, the stress and risk was worth it. “We realized that we had a special relationship. I know that I have input on the fish that I am receiving,” he says. “We inform each other’s businesses.”

But perhaps more important here is Marhefka’s fervent commitment to sustainability. Since the early 2000s, he has worked to create and preserve marine-protected areas — no catch zones where fish populations can rebound. This dedication, not to mention increasingly strict quotas from the Department of Natural Resources, means that Marhefka doesn’t just fish for the favorites. “People say to us, ‘All I want is grouper!’” he says. “But it’s up to us to educate the consumer.” Marhefka brings in everything from king mackerel to amberjack. He educates his chefs and, by extension, the consumer. Hopefully the consumer walks out of a dining experience with an appreciation for a new kind of fish—but also an appreciation for its narrative and habitat.

Photography by Oliva Rae James

Tarvin Shrimp

Cindy Tarvin’s shrimping boat, the Miss Paula, is moored a few docks down on Shem Creek. When we arrive, she is standing at the doorway of a large packing shed, sorting orders for the day to come. The Tarvins run a small retail business out of the shed, but 70 percent of their inventory goes to local restaurants. Their fresh, preservative-free, wild-caught shrimp are a hot commodity. Lata’s entire philosophy, the essence of his brilliantly uncomplicated food, is the quality and integrity of his ingredients. So purveyors like Tarvin Seafood are the lifeblood of his business.

In today’s market, the shrimp Tarvin sells are nearly impossible to find. Most people, she tells me, don’t even know what shrimp actually taste like. “It’s like when you taste a garden tomato for the first time and realize what a tomato is supposed to taste like,” she says. “It’s the same with shrimp.” There are two types of preservatives on the market. The first, a citrus-based option called EverFresh, does not require labeling. The second is called sodium bisulfite, which the FDA requires to be labeled, and that, Tarvin says, is what most people know as shrimp. As she describes the texture of a bisulfite-treated shrimp, Lata emphatically shakes his head. “That shrimp tastes like it could be from Mars,” he says. “It’s not even the same thing.”

But this commitment to preservative-free, wild-caught shrimp makes the business infinitely more complicated. Wild shrimp populations fluctuate without warning, and the Tarvins have to simply ride the wave. Starting in July of last year, for instance, the shrimp just disappeared.

“You can’t make the shrimp appear,” she says matter-of-factly. “It is what it is.” That uncertainty, however, is mitigated by committed buyers. Between his two downtown restaurants, Lata is committed to buying around one hundred and fifty pounds of shrimp per week. Tarvin shrimp is on the menu year-round, unless there’s a shortage. For both Tarvin and Lata, the integrity of the product and the small local team is worth the perils of wild-caught shrimping. Naturally this means that Tarvin shrimp come at a premium. “We don’t try and be the cheapest, we just try and have a nice product. Whether it’s to a big buyer like Mike or the small guy down the street.”

As we say goodbye and walk to our cars, Lata comments, “The Tarvins represent so many good things, you know? People are still working on our waterfront. It’s a net plus for the ecosystem.”

Barrier Island Oyster Co.

We stand on the old East Coast Seafood Dock in the midday sun, slurping oysters as fast as Josh Eboch and Jared Hulteen can shuck them. “There’s just a different taste to the South Carolina oyster,” muses Hulteen. And although my palate may not be sophisticated enough to recall comparisons, the flavor of each Sea Cloud oyster is like an explosion of taste — cold, fresh, and briny. “This is a great study,” agrees Lata. “The merroir — how nature influences the species.” Indeed, there is nothing quite like a South Carolina oyster. In the wild, they grow intertidally — on the shoreline — as opposed to subtidally. And if you cruise the tidal creeks and rivers of the Lowcountry at low tide, you can hear them clicking and burbling in the plough mud. “Oysters are actually considered a keystone species,” says Hulteen. “Over one hundred other species depend on oyster reefs in South Carolina. If you take oysters out of the ecosystem, you eliminate life in the estuary.” For that reason, Hulteen and Eboch raise oysters in floating cages and leave wild populations to do their work.

They started the permitting process in 2015, but it wasn’t until 2017 that Barrier Island Oyster Co. sold its first oyster to a restaurant partner. Building the business from scratch took time, and Hulteen and Eboch placed a high importance on doing things right, on the integrity of their product. “We have been very selective about who we sell to,” Hulteen says. “Putting our oysters in the right hands is so important. If you sell our oysters, you sell our message and what we’re doing with sustainable farming.”

Lata’s partnership with Barrier Island Oyster Co. fell easily into place over this shared ethic and vision. After just one year, Sea Cloud oysters are a constant at Lata’s restaurant The Ordinary. That relationship is everything to Lata. “Once we get comfortable and go through the growing pains together…for me that’s like becoming blood brothers,” he says. “It’s all about trust.”

And as more oyster farms show up in the area, Hulteen and Eboch are committed to leading by example. They are very involved in the South Carolina Shellfish Growers Association (Hulteen is the current president!) and hope to create a culture of sustainability in the industry. “We want to represent the industry well, because there’s a future for all of us,” says Hulteen. “We want to be here for a long time.”

GrowFood Carolina

As we step into the yawning entrance of the GrowFood Carolina warehouse, Sarah Clow meets us with a smile and a hug. She and Lata instantly dive into a conversation about a farmer whose satsumas are particularly beautiful this season. As they talk, Clow leads us into a massive cooler and pulls various boxes down from the high shelves — chestnut mushrooms, crispy lettuce, meyer lemons, and bright, multicolored carrots. It’s fascinating to see Lata in this setting — he is instantly focused, touching everything, inspecting, smelling.

GrowFood launched officially in October 2011 to support local farmers with sales, marketing, warehousing, and distribution as a farmland preservation initiative. Currently they connect over one hundred growers with more than three hundred restaurant, grocery, and institutional partners in Charleston, Columbia, Greenville, and Savannah, and they have led the formation of a statewide food hub network in order to expand the impact. Lata has been on the GrowFood committee from the beginning and was instrumental in its development over the last eight years.

Before GrowFood, there was no middleman to manage relationships between farmers and restaurants. If a local farmer wanted to sell to downtown chefs, it meant driving into town and making individual deliveries. Farming is a labor intensive and demanding endeavor even without all the logistics of scheduling, invoicing, deliveries, and generating new business.

“That barrier to entry is so high for farmers,” explains Lata. “Growers are still rotating in and out all the time.” Buying from local farmers is still wildly time-consuming from the restaurant side as well. In the days before GrowFood, it was very difficult for chefs who wanted to introduce local foods onto menus to coordinate deliveries from multiple farmers a day. This ad hoc model was well-intentioned but grossly inefficient.

Enter GrowFood Carolina. The organization acts as a hub for farmers and chefs alike. Farmers deliver to a single location. Chefs buy from a single location. A chef can deliver feedback to the farmer through consistent, organized channels. Administrative tasks like invoicing and payments are systematized and streamlined. In addition, the GrowFood team works directly with farmers to improve their practices and plan crop production. “We do an intense yearly assessment,” explains Clow. “What is their cost per box? Can they push their season by two weeks? Is it time to get a high tunnel? These are important questions that make a big difference in shaping their business.”

And for a chef, GrowFood is an incredible resource, a one-stop shop for local produce and a middleman for all manners of logistics. GrowFood not only helps bolster the viability of local farmers, but they also hold them accountable to a system, a calendar for growing and a structure for selling. This consistency is crucial to restaurants. It means that chefs can count on quality local ingredients for their menus and develop more synergistic partnerships. “The name of the grower and where they are growing is on every box in the cooler,” says Clow. “Even if a chef never meets the Watsons, we’ve talked about them, the chef understands their story, and knows they are getting Watson eggs.”

All in all, the hub allows both restaurants and farms more time to focus on what’s important—the quality and integrity of the food. Formal feedback allows both parties an opportunity for a better perspective on their process and the role they play in the larger market. As a board member and stakeholder, Lata is still very much invested in GrowFood’s success. A few months ago he spent two days in the warehouse working with the GrowFood team on quality control. For him, the GrowFood model bridges the gap between chefs and farmers in the most sustainable and mutually beneficial way.

Shaping Kiawah’s Dining Culture

Chef Lata has worked closely with the Kiawah Island Club team to fine-tune every last detail of the restaurant. Before its opening, he said “I think we’re going to deliver a beautiful restaurant. I am grateful to the Club ownership for recognizing the importance of local foods and supporting my creative vision. For the last twenty years, I have curated an amazing family of purveyors that represent the best of our local resources.” Since its inception, the B-Liner has quickly shaped the dining culture at The Beach Club and the rest of the Island.

If the B-Liner has piqued your interest, we invite you to come taste its incredible dishes for yourself. Visit Kiawah Island and allow us to show you everything the Island has to offer. Explore the beautiful communities of Ocean Park and Cassique, and tour one-of-a-kind homes as part of Front Nine Lane, The Cottages at Marsh Walk, and The Estuary, to get a sense of what Island life is like. Click below to start planning your visit.